Martin Stephenson had his rather more than fifteen minutes of fame in the late eighties and early nineties. His first albums were critically applauded and sold well but then things changed. How did he get into music in the first place?

“My first step into music was when I was eleven. I entered a penalty competition at school and I won.” Excuse me? “There was a guy my age who was really tall and a goalkeeper and he collared me because I could take penalties. We got together every Saturday for him to practice and he told me to come along to the scouts because there was a guy who ran it who was really special. I went along and met this guy called Jim Sixsmith and he became a guru to me. He put a table tennis bat in my hand and played The Doors to us, Santana, Zappa – a great musical education. He was into getting rough young kids interacting and supporting each other.”

So Martin was a rough kid? “I was born in a rough environment but I was always a deer. I wasn’t a wolf but I thought I was a wolf because I was running with the wolves but one day at the watering hole I caught a glimpse of my reflection and I saw Bambi there.

“When I was fifteen Punk came along and even to my guru Punk was shite but to me it was like being reborn. I thought at that time you had to be a genius to play music but Punk gave you the confidence to have a go and be primitive so I started as a guitarist. I was a punk guitarist from fifteen to seventeen or eighteen but punk started to move on into New Wave and then I started to educate myself. I bought a classical guitar book, a jazz guitar book, a folk guitar book and I would usually get through the first ten or eleven pages and get bored.and go and put the kettle on. It was the journey from giving up on a classical exercise to putting the kettle on where I would meet conceptual art.

“I became a songwriter and I‘d have little bits of jazz, blues, country – jack of all, master of none – I just used what I had. I was a guitar fan and a bit of a poet and it just started merging. I’d probably been taught how to channel as well so every time I wrote a song I was bringing it through the crown chakra, I wasn’t getting in the way. I felt that I didn’t have the craftsmanship to get in the way but that was giving me a head start with the songs.”

Martin’s band was, and still is, The Daintees. “They were people I just bumped into, they weren’t session people. Our second drummer was from Billingham and he was, like, fifteen years older than us and he’d worked with Chris Rea – we called him ‘Class’ but he thought I had something. I’d done a lot of busking and I’d learned how to connect and you have to find a way to connect and share whatever you’ve learned on this journey.

Martin Stephenson and The Daintees signed to the nascent Kitchenware Records. “They were just a young team putting a little label together, inspired by Postcard Records probably.” Martin’s first two albums, Boat To Bolivia and Gladsome, Humour And Blue were released to excellent reviews and good sales.

Martin Stephenson and The Daintees signed to the nascent Kitchenware Records. “They were just a young team putting a little label together, inspired by Postcard Records probably.” Martin’s first two albums, Boat To Bolivia and Gladsome, Humour And Blue were released to excellent reviews and good sales.

“It was a phenomenon, but my manager was a clever lad with a lot of vision and he wanted to have a great label in Newcastle – he found Prefab Sprout who I was gigging with in 1978. I always thought they were kind of odd but Paddy McAloon was a great guitar player. He would play very odd chords, he was very left field. He had a Peter Hammill vibe about him. We got picked up because we were busking and our manager liked that but he liked Prefab Sprout for totally different reasons.”

In 2012 Martin and The Daintees re-recorded and toured Boat To Bolivia and he is now repeating the process with Gladsome, Humour And Blue.

“I want to do all four. [The others are Salutation Road and The Boy’s Heart.] The main reason was to revisit and reconnect after thirty years. It’s a bit like getting your old BSA Bantam out of the garage and sitting on it. I thought that when I was fifty-seven I would have all the answers and I was thinking ‘yeah, I would have done that but I’d never have thought of that now’.

“To me apprenticeship is everything. To travel with John Martyn, although he was difficult at times, was so valuable. It was like being a painter and getting a chance to be with Van Gogh, getting your apprenticeship with the great ones – I always had an awareness of that. When I did Gladsome the night watchman at the studio was Speedy Keen of Thunderclap Newman and I spent as much time hanging out in the kitchen with Speedy talking about Jimmy McCulloch as I did recording. That was really precious to me.”

There was another reason. “On my third album there was song called ‘Morning Time’, just a little finger-picking thing I put down, and nobody ever noticed the song. A few years ago someone in Australia got in touch, wanting to use it in a Nutella advert. I was just at the point of getting all the rights to my songs back so I said ‘it’s nice of you to offer but give it someone else’. They wrote back offering A$100, 000. I’m not motivated by money but when that came I thought, ‘well, I can put my youngest daughter through college’. I was surprised but I also panicked as well because if I’ve got two grand in the account, I’m happy. This came so I bought three vintage guitars, bailed a few mates out and put the kids through college just so it would go away again.

“It made me think. I’ve got kids but I can live like a hippy and half that money went to Warner Bros. and my old management. If I’d re-recorded it I would have got 100%. I don’t normally talk like this but it made me think and I set about re-recording them just in case anything like that ever happened again.”

What differences does Martin hear between the new and old versions?

“Just having a bit more awareness. When I was younger I wanted some strings because I’d never worked with strings. Musicians sometimes come to that; even Buddy Holly wanted to work with strings – it’s something you want to fulfil. I had my friend, Virginia Astley, doing some flute – it was just what was going on at the time and I was trying to develop as an arranger. But when I went back I thought, ‘no, I don’t need to do that. ’The Old Church’ had strings on – don’t need to do that, I’ll just use a Memory Man guitar pedal and put on some beautiful unresolving chorus harmonics and let them float around.”

After four albums Martin left the label. The official story tells of falling sales but Martin remembers things rather differently.

“I consciously left. Kitchenware were really family. I had no interest in anything except music and I thought I might have a chance to make a couple of singles before they realised that I’m an imposter and send me back to being a carpet fitter. I had a lovely time – we were just young people helping each other – and when the majors came in, which is a natural part of the process because the independent company had to go and get help so it had to license its artists out, then I saw a change.

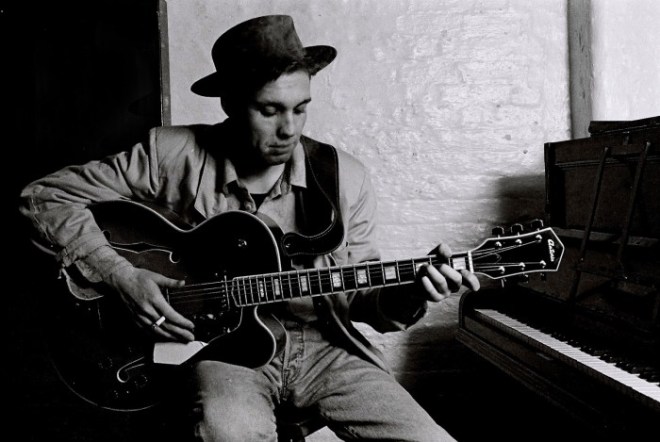

“The first time I noticed a change was when I came into the office one day and I was told ‘you can’t come in today, Prefab Sprout are looking at their album sleeve’. It was like being in a happy family and then being told that you can’t go in your brother’s bedroom. At the time that really hurt me and I thought ‘here comes the death of the family, here comes the reality. We’re going to see who’s who now’. As it started to grow my spiritual heart was dying. It took me up to 1992 to really cut it all off – I don’t blame anybody now but at the time it was excruciating – but I stepped into poverty and let go of everything…I came north with a bin bag of clothes and an old Sobell guitar and rebirthed.”

Martin’s next album was the solo High Bells Ring Thin and I recalled a story about the original tapes being destroyed in a fire and how he was forced to re-record the whole thing in a minimalist style.

“I think that was something to do with my manager – he used to make up little dramatic things like that. It was just something that I wanted to do. The tape of every song for a major album I’d take in to the manager or the band and it was ‘God, have you not got any happy songs, Martin?’ So I had a lot of songs that wouldn’t get passed; there was a whole area of my song-writing that they didn’t get. I did it myself and never got any support – they probably hadn’t even listened to it.”

The album was recorded in a studio in Newcastle owned by Brian Johnson of AC/DC. Martin recalls that Brian was away most of the time and left his wife to run the studio. Mond Cowie of Angelic Upstarts was the engineer and Chas Chandler, who Martin greatly admires, was often around. Those years, however, were a crisis point in his life. “Initially it was the divorce from my manager, who I love dearly but we’re different and it was good for him that we parted. We just needed different things.”

Martin now lives simply in a house overlooking Cromarty Firth where everything he needs seems to be within arms’ reach. He hasn’t stopped writing or recording, indeed he has released a prodigious number of albums over the last twenty-five years. “Everyone I work with have vocations. They are probably better earners than I am but we share and we’re working on a different level. I’ve got a lawyer, just for when I need him, and he got all the rights to my songs back.”

What I, and I suspect many others, found hard to figure out was how this different level of working has managed to sustain Martin for so long.

“Once the budgets go away the creativity fills the hole. Big budgets and all the trappings are what 80% of the business are working towards. I was always working the other way. I was lucky, I had an education before all this so once I got into no budgets – not low budgets, no budgets – and physical poverty but spiritual wealth I was really free. I can make a really beautiful record on a really low budget and have a phenomenal experience. I can recoup my budget by selling ten albums.”

Yes, but…

“If your demands aren’t super high and as long as you can keep your ego out of the way. When I left the industry I went back to busking and people said ‘you can’t do that, you’ve made albums’. The budget for my third album was £140, 000 and if I re-record Salutation Road, which I aim to do in the next six to twelve months, I’ll go to Newcastle in Stephen Paul Cunningham’s kitchen and the budget will be about a grand.

“I did a project called The Incredible Shrinking Band, I put my guitar and vocals into a WEM Copycat through a WEM amplifier and pressed Record on a mini-disc and I actually took a phone call during the real time of the album and I said ‘I’ve got to go, I’m in the middle of recording an album’.” If that sounds like a tall story let me assure you that the track in question is available for all to hear. “It’s got something about it that Salutation Road hasn’t got and I sold one copy and I broke even.”

I must confess that I lost track of Martin until the Bayswater Road album appeared last year and I realised what I’d been missing. The variety of his musical styles is remarkable: finger-picked guitar, pop, rock and alt-country are all in there somewhere. He doesn’t see any restrictions on what he does.

“I think that came from being a guitarist, trying to learn different styles. On Boat To Bolivia I can hear a series of guitar exercises. ‘Coleen’ probably came from The Mickey Baker Jazz Guitar Book – the opening chord is like that.” Martin demonstrated but as I didn’t record the video part of the conversation you’ll have to take my word for it. “That’s what I love about John Martyn: he’d tune a guitar to a chord and fiddle around to find what sounded nice to his ear. He was fearless.

“Some people say ‘you haven’t got a musical direction, you haven’t got a formula’ but, to me, that would be very boring although I love Status Quo, one of the great formula bands. If it were to be seen as a strength I’d say you could take three songs from a thirty-five year repertoire and the range is phenomenal and that comes from channelling, it doesn’t come from me, I’m just in service to it. I’m not some kind of visionary but anything spiritual is simple. We all know the truth – there’s nothing I know that you don’t know; it’s all about love and being open but it’s prickly down here. One thing I learned is ‘don’t fill the whole canvas, leave some space for the listener’.”

Martin Stephenson lives a life that some of us might find challenging, others would find idyllic but it suits his personal brand of spiritualism which owes nothing to one particular faith or philosophy but something to all of them. The essence of it is that he doesn’t have to deal with money any more. I had to ask the silly question, however – what’s the attraction of the Scotland?

“When I first started coming to the Highlands I connected with a guy called Rob Ellen – he’s like a cross between Merlin and Arthur Daly – he’s an agent who’s always been skint [Rob also helped found the Belladrum Festival] and he’s the guy who took Julian Cope around all the Neolithic sites. He was probably the only guy who would really listen to me. We’d play little islands; it was like ‘we just played to ten people last night but there was a seal sanctuary on the side of the house’. To me it was like being reborn as a troubadour.

“I met Gypsy Dave Smith in the mid-80s – great blues player – and I went under an apprenticeship with him. We connected. Gladsome, Humour & Blue has Gypsy Dave all over it and we got reborn together; it was like getting back to the 60s so he attracted me to the Highlands as well.”

Martin doesn’t have a studio at home, at least not as such, but his kitchen seems littered with equipment and he’s happy to record people for free as well as making his own records. He does travel but it’s easier for him to fly from Inverness to play a gig in Bristol than to undertake the six hour drive home to Newcastle. I’ll leave with one thought that really sums up our talk and Martin’s view of the world.

“The [music] industry can do so much magic and crap but it’s the Devil’s work and there’s this other place where they can’t touch you and they still can’t stop us meeting up.”

Dai Jeffries

Artist’s website: http://www.daintees.co.uk/

‘Wholly Humble Heart’ – live:

News about Gladsome, Humour & Blue 30: https://folking.com/martin-stephenson-re-records-gladsome-humour-and-blue/

We all give our spare time to run folking.com. Our aim has always been to keep folking a free service for our visitors, artists, PR agencies and tour promoters. If you wish help out and donate something (running costs currently funded by Paul Miles), please click the PayPal link below to send us a small one off payment or a monthly contribution.

Thanks for stopping by. Please help us continue and support us by tipping/donating to folking.com via

Thanks for stopping by. Please help us continue and support us by tipping/donating to folking.com via

You must be logged in to post a comment.